Before there was Stanley Tucci: Searching for Italy on Thee Cable News Network, there was Stanley Tucci as Secondo, a younger brother who had a vision for a successful, true Italian restaurant on the coast of New Jersey. Big Night begins in the middle of the restaurant’s failure—the bank will foreclose, and older brother Primo, the chef, refuses to bend to easy money: serving spaghetti and meatballs together, or doubling up on starch, like risotto with a side of pasta. Customers are few. Their lone regular, a painter, pays with his art. Primo, the older brother and chef, played by Tony Shalhoub, warmly accepts painting after painting, meal after meal.

“The movie exists in the real world,” Roger Ebert wrote in his 1996 review, “where you can go broke selling great food.” The restaurant is rapidly losing money, and the brothers are denied loan after loan. Secondo desperately turns to the owner of the more successful Italian restaurant next door, Pascal, who calls in a favor to his “friend”, the famed jazz legend Luis Prima. His idea: Prima’s visit to the brothers struggling restaurant will inspire its renaissance. But it is the real world, where the allures of wealth, success, and possibility—quintessentially “All-American” promises—are revealed as myths, empty as Pascal’s favor. A smarmy Cadillac salesman (Ian Holm) has that specific attractiveness that Jon Hamm has in Mad Men, a charisma that’s perfectly undercut by a broken arm, wrapped up in bright white plaster. Secondo asks how he did it, and Holm’s character responds, “I don’t know.” We know that this can’t possibly be true—and in the omission we imagine him doing something fantastically stupid.

The majority of the film takes place in a day, leading up to the big night where Luis Prima will come. And just as the record player spins, so does Secondo with his schemes to make the night go as smoothly as possible. Then there is Primo keeping watch of, among other things, the crown jewel of the night: the Timpano, a special recipe from their hometown.

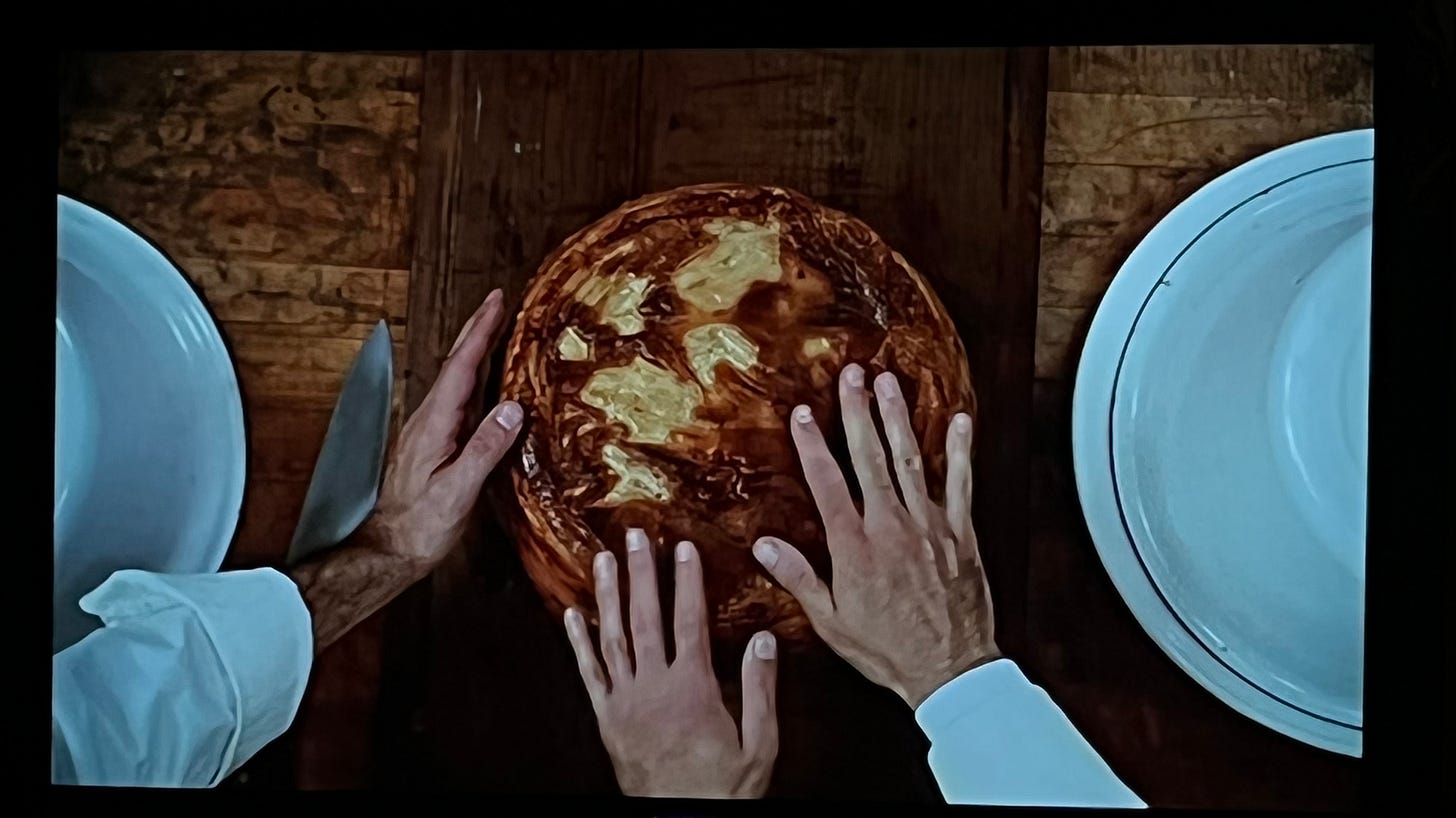

The Timpano is essentially a huge hunk of Noodle with lots of more Noodle inside of it: Pasta dough is rolled out like pastry and fits a Dutch oven. More pasta, meat, and lots of other delicious things are stuffed inside, like hard boiled eggs, ricotta, salami... It’s called a “timpano” like the drum or timpani, because when you tap on it and it sounds hollow, it’s ready—but cut too soon, and it falls apart. It takes all day to make, and it’s really only for special occasions, like a Big Night, because it’s such a pain to make. (There’s a Timpano alla Big Night from Tucci’s Cookbook and NYTCooking, and a Bingeing with Babish video as well as a TASTY one, because video is exactly the sort of thing this dish is made for.)

The climax of the film hangs on that specific moment at a dinner party that everyone knows, where the aperitivo hour has gone on little too long, and you are waiting, albeit gleefully, for whatever reason: the food to be ready, the guest to arrive, or sometimes even to remember that time still moves. In Big Night, the guests are waiting for Luis Prima, but the brothers are waiting for all the answers, and in the meantime, everything happens. Tony Shalhoub finally courts his crush, the flower shopgirl (played by Alison Janney, who, crucially, is wearing a corsage), the only way he knows how, by feeding her. (“To eat good food is to be close to God.”) Secondo’s mistress (Isabella Rossellini) cares for Minnie Driver (Secondo’s girlfriend) when she gets sick outside, and then they talk about cowboys. The Cadillac salesman gets too drunk. Everyone dances. And then, succumbing, they quiet to sit down to eat. Finally, the timpano is served, which had been cooking all of that time.

Daniel Lavery wrote a tweet that “we don’t need another Mario movie. we have Big Night” And it’s true—Shalhoub’s Primo scurries around with such chefly purpose and a mustache that is so very broom-like, I half expect their real names be revealed as Mario and Luigi (don’t tell me otherwise). The brothers encircle each other mostly in argument, but the swirl of their frustration stops when they prepare to cut into the Timpano, worried it will fall apart, but needing desperately to serve it, to satisfy. It is a feeling that you know well if you have ever cooked for a group, whether at home or in a restaurant: to see out something out that you aren’t quite sure is ready yet, but that you must trust in your gut is. It is, like life, the push and pull of anticipation and denouement, the chance that you might fail as much as you succeed—and anything is possible, no matter how good you are. To open up the drum and see inside is the risk, and to trust that you can rebuild it is the hope. The Timpano scene isn’t even my favorite one of the film—the final scene is the one I have always wanted to write about, but perhaps I’m afraid of opening up that drum just yet.