It’s Saturday in April, and inboxes are aflood with TurboTax reminders. (The last time I dropped in was to share a Q&A with baker Carla Finley—Happy birthday to Apt. 2 Bread, which turned two this week!) Since then, I’ve been writing my Master’s thesis on ramps (Allium tricoccum), to defend just in time for ramp season. Right now, bright green leaves are shooting up from Maine and Canada to Michigan, Iowa (yes!) and south to the ridges of Alabama and Georgia.

Ramps, or “wild leeks”, aren’t just any wild onion. These little alliums are deliciously pungent, a garlicky tonic of sorts, but they are also characterized by an enchantingly slow and mysterious life cycle. It’s because of this, coupled with demand and harvest driven in part by high ticket restaurant experiences, that they’re also at-risk. Here’s a little snippet from my thesis about what makes them unique:

In early March—depending on the region—the plants emerge. They start out as small green shoots, and then continue to develop rapidly with the increasing springtime temperatures and limited overstory. James L. Chamberlain, an agroforestry expert and author of numerous publications on ramps, explains that the majority of ramp growth at this time is characterized by a unique set of factors: it’s the only time of the year that the land is thawed, lacking snow, with abundant sunlight. He says, “What happens if the snow melts off, sun comes out, starts warming up the soil, and the plants emerge? They get all this sun up there, and they're just photosynthesizing like crazy, just grabbing all these photos and then growing until… the canopy closes.” At 90 percent closure of the canopy, leaves die. It’s at this point that the plant stays alive the only way a spring ephemeral can: by consuming itself down to the bulb, which remains underground til the following March.

But because ramps generate one of two ways, both by bulb division where patches are healthy, and going to seed, there’s a lot that must happen between the emergence of the leaves and their senescence. As the leaves start to drop back, which usually happens in May or June, a flower stalk starts to emerge from the bulb. It flowers and goes to seed in July and August. The seeds drop around September and October. The remnants of the flower stalk, devoid of flower or seed, is called a scape.

If those seeds do not germinate the following March, they either germinate the next year, or not at all. The literature says that it is five to seven years before the germinated seed becomes a mature, thriving, plant that is big enough to harvest multiple leaves.

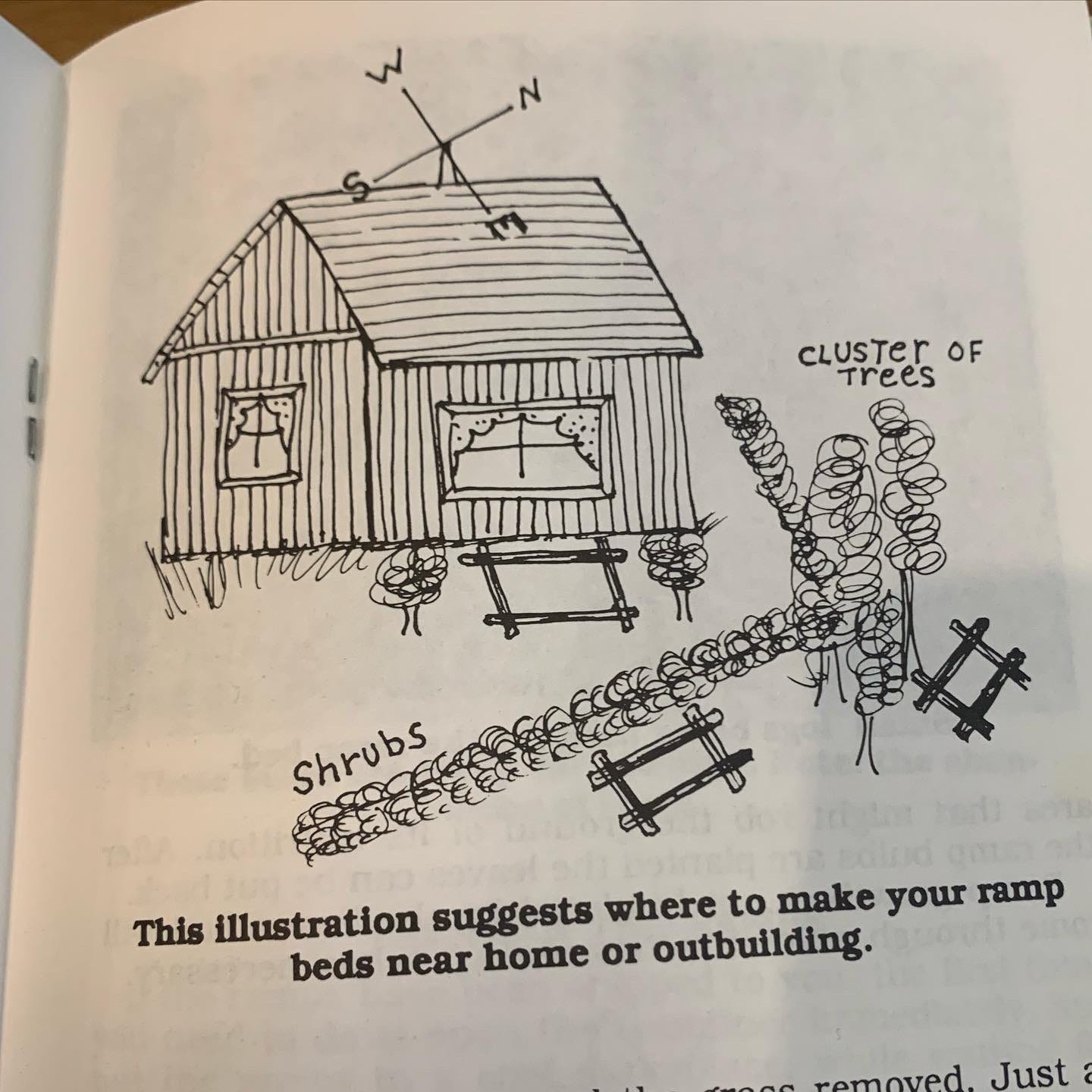

If you forage them, snip just a leaf or two each. And if you do buy ramps at the farmers market with a bulb and root hairs on them, consider keeping the leaves and replanting them. They like east facing shade and hardwood trees like poplars, but even planting aside a barn, shed, or house would do.

To taste:

If you’re bold, eat ramps raw, or try a classic dish: fried with butter and potatoes or scrambled eggs. There is, of course, a ramp tart option for the footloose and fancy free.

To read:

Kitchen Person by Dana Tortorici for SSENSE

In “Clothes”, a 1974 poem about what to wear Anne Sexton suggests her painting shirt, “Spotted with every yellow kitchen I’ve painted.” She writes :

God, you don’t mind if I bring all my kitchens?

They hold the family laughter and the soup.

To listen:

Cooking playlist updated!