#56: Frank Hurricane on the Mystical Shoneys, Pilot Mountain, and Philly Cheesesteak

"The world is open to you to do whatever... You just have to open yourself up to it, and then it just goes down."

About an hour before his set, I met Frank Hurricane, buoyant in bright fluorescent Hoka’s. We were at Saturn, Birmingham’s beloved music venue that is inexplicably but impeccably designed after a Trekkian space Odyssey. I’d listened to Frank Hurricane’s records but I’d been advised that his shows were a living and breathing thing—something otherworldly—and the setting felt appropriate to make up for the fact I didn’t know what I was in for. My favorite song hence was “Holy Mountaintop Rainstorm,” a short, echoey hymn that sounds like it was cut in a cave with a lost recording of a Sargeant Pepper era marching band. I was excited to hear his more typical stuff, in person. (Later, the show itself lived up to any expectation. It was a small crowd, gentle but engaged. Frank Hurricane laid a path of tunes like a time traveling, finger-picking Bard in tie-dye.)

We spent the first good chunk of our conversation talking about all the places we’ve lived and our favorite sandwiches, but we mostly talked about mountains and stories. Born in Durham, North Carolina, Frank Hurricane moved around a lot as a kid (from Chapel Hill and Fayetteville to Columbia, South Carolina, and eventually to Johnson City, Tennessee where he stayed for a while). He started playing music out of the DIY scene in Atlanta before starting his touring life, landing for a time in Boston and New York City, where we discovered we overlapped. After some time back south in Athens, Georgia, and eventually Chattanooga, Tennessee, he now lives in Philly permanently. “I’m not going anywhere for a hot minute from Philly,” he tells me, citing the openness of the music scene—and the sandwiches. Our conversation been edited and condensed for clarity.

FH: It's the best sandwiches in the world, and I don't think anybody can really argue with that. There’s all kinds of stuff, but the sandwiches are the best: the cheesesteaks, the chicken cutlets, the Italian sandwiches…

But I want to be able to—at any moment of my life—order a full Pizza to the Dome that I know is going to be awesome. That's important, and Philly is loaded with pizza. And the music scene's crazy good. I listen to all kinds of music, but I would say that most of the shows that I go to are free jazz shows, noise shows, or finger-picking, experimental folk shows. A bit on the more psychedelic side, the more mystical side. Philly has all that stuff.

CJ: What are some of the venues that have free shows?

FH: So many. West Philly has all these house shows. I do a lot of shows at my friend's house called the Surf Shack. It's a basement that my old friend from Boston—then New York, and now Philly—lives at. There's a professional surfer guy that lives there. It’s his house, so it's called the Surf Shack.

CJ: That's awesome. It's not surf rock, is it?

FH: No, no. The guy who's the surfer is a classically trained musician. They have a grand piano in the house and his sister plays cello, a virtuosic cello player. That’s what Philly's cool about: There's just so much stuff I love. [But] the South is where I'm from. It's what I love the most. It's where I feel most at home.

CJ: Yeah, I wanted to ask about that. A friend of mine in Athens [Georgia] pointed me to your music. It's something that I felt really drawn to: the names and places in the natural world and in the south in your songs. Can you tell me a little bit about what those places mean to you, that you invoke?

FH: When I'm making music, I'm telling stories or I'm capturing the vibe of a place. To me, the mountains of the south and all the different little nooks and crannies in the towns—especially the trails, the peaks, the creeks, and the different swimming holes and stuff—those are the places I think of most of the day. Most of my life I'm thinking of these places, and the music can transport me to those places, and hopefully transport other people to those places, too.

I was always outside as a kid, going into people's backyards, and finding weird woods, and trails, and old tree houses in the woods. Looking for cool, weird stuff out in the woods and in nature. Loving abandoned stuff, ghosts, spirits, haunts and unhaints—all that kind of stuff.

When I moved to East Tennessee [as a kid], I was already big into outdoor stuff, but I'd never lived in the mountains before. I didn't realize that there's these freaking huge waterfalls and amazing trails. There's this trail that's 2,200 odd miles going through the mountains that you can hop on pretty close to town. Once I started going out, it blew my mind. It made me happy. It made me feel right. It made me feel like I had found something that I was good at, that I loved, that made me feel in touch with spirits and God. I like to try to get people to feel that themselves [in music], whether or not they can go out there. Especially if [they] grew up, in a big city.

CJ: How did you decide to take that wonder from experiencing these things to putting them to song? When did that happen?

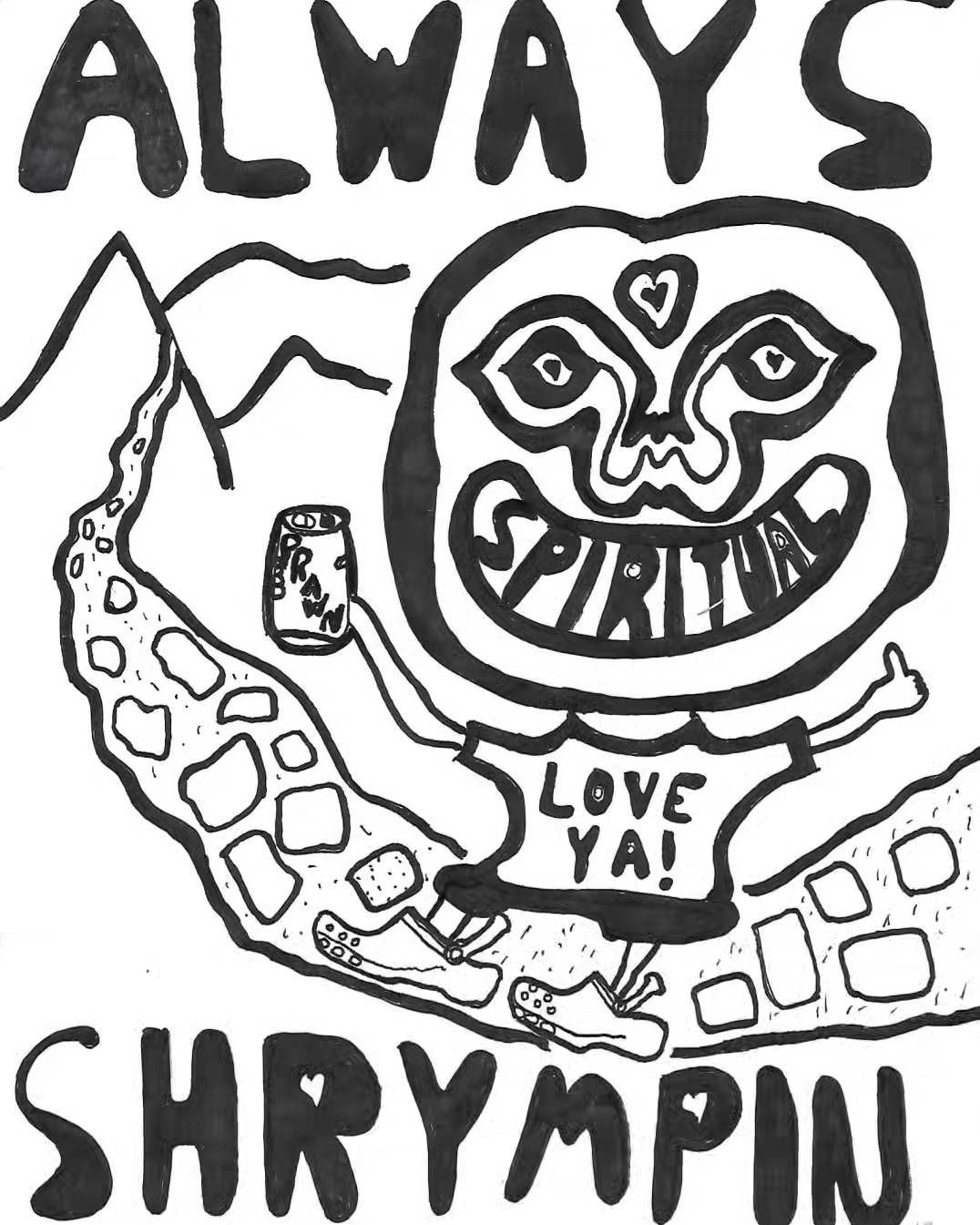

FH: I had started [writing songs about stuff I was doing], but I wasn't a serious musician at that point. I knew I loved [playing music], I thought it was cool, and it made me happy, but I didn't [start performing] until I was [about] 23 in Atlanta. I started meeting some people who live here in Birmingham, like this guy Milton and his homie Pony Bones, and all these psychedelic nutty shrymps that were so off-the-chain and very inspiring. [They] were into all the same stuff I was into. I didn't realize that you could play music and play house shows. Your average Joe, they think that to play music, to go on tour, you have to be playing big-ass places only—like here tonight—but in reality you can go around and you can do anything. The world is open to you to do whatever.

“Your average Joe, they think that to play music, to go on tour, you have to be playing big-ass places only—like here tonight—but in reality you can go around and you can do anything. The world is open to you to do whatever.”

I went to go see Jack Rose, a famous finger-picking guy from Philly who passed away—he was playing at eyedrum in Atlanta—and Pony Bones was playing. He was completely nuts. Insane noise. Banjo player. Throwing things at the audience. People were like, There’s some dude ripping up newspapers and setting them on fire inside the place. There was this twisted-ass bro playing a harmonica who looked hainted as hell. There was some guy with a guitar that sounded horrific, and it was amazing.

I went up to the homie after, and I said, That was life-changing ,and he was like, You want to play at my house? I was like, Yeah. So I started playing these shows, and next thing you know, I went on tour with him. Then I started going on my own tours, and playing night-after-night, horrific gigs, but having the best time also. Finding things, meeting people, and learning things. I fell in love with playing. It builds upon itself. You do things, you meet people. You see life-changing things, and then you write songs about them. On this tour, especially, I've been getting lots of new tales and inspired about new songs, because I've just been seeing so much cool stuff. You just have to open yourself up to it, and then it just goes down.

CJ: You mentioned meeting these guys, Jack Rose, Pony Bones, and others—calling them ‘shrymps.’ It comes up a lot, and I really like that. Can you tell me a little bit more about what [the term ‘shrymps’] means to you?

FH: ‘Shrymps’ is kind of like [how] in Philly, there's this word, ‘jawn.’ It means everything. ‘Shrymp’ is the same thing. ‘Jawn’ could be bad stuff, [but] ‘shrymp’ can't be bad stuff—it's only good stuff, cool stuff, things that you like. Things that bring humanity closer together, things that connect. Positive, holy stuff, that's Shrymp.

CJ: You mentioned the landscape of Tennessee being really inspiring, and it sounds like Johnson City was the first place that you lived and experienced that.

FH: Well, I was inspired a lot, because my grandpa lived in Wytheville, Virginia.

CJ: I know Wytheville! Did you ever go to the Bob Evans in Wytheville?

FH: I've been by it.

CJ: It was my favorite restaurant when I was growing up.

FH: That's a mystical spot. I never went there. I always seen it. The Mexican place next door—I ate it a thousand times. And the psychedelic Shoney's up on the hill, across from it—I ate it a thousand times. And there's that psychedelic German theater that's also over there. It’s a German [restaurant] dinner theater place called the Wohlfahrt Haus. I want to go there. It looks insane.

My dad grew up there, my grandpa grew up there, and my grandma grew up there, lived there. They're buried, my grandma and grandpa, in Rural Retreat, which is the town over.

CJ: I know it well.

FH: When I was a child, we'd drive from North Carolina to go there. I'll never forget the big psychedelic peak of Pilot Mountain. You come around this bend towards Chapel Hill and Durham from Wytheville, and it's a huge view—expansive—looking over the valley, and you see Pilot Mountain distance.

They used to have steps that were stuck in the side of the rock. There was staircase built into the side of that whole thing, and you could swirl, like a spiral staircase, around it. My grandma used to go all the time. [She] grew up going there, and there's pictures of her climbing up the mountain. Now you can't go up to the peak, really. It's blocked off. The rock climbers do it, I think, but I don't even think you're supposed to.

I remember one drive, it was so foggy. We were heading back home to Fayetteville, and it was so foggy that we couldn't drive. The road was shut off because of the fog and I was hoping I'd miss school the next day—but it cleared up eventually. Fog is really incredible. It totally obscures everything. There's nothing you can do about it.

CJ: What for you makes a live musical experience different from a recording experience?

FH: I take you on a journey, a mystical journey, with stories intermingled with songs. It’s a trip. When I start rocking, people just get into it, and then 45 minutes later, you come out of it. It’s a mystical journey. A record is kind of like that, but with a record, it's just the songs that are doing it. In the live show, it’s the stories and mystical interludes, and whatnot. To me, the live experience is what my music is all about. I want to make albums that are just for listening too, but the live show is where it's at. It's a journey, a holy story.

CJ: How is it holy to you?

FH: I think everything's holy, even the bad stuff is holy. But not shrymp. Shrymp is only the good stuff.

CJ: Only the good stuff.

FH: Only the good stuff.

CJ: What is your favorite sandwich?

FH: Philly cheesesteak at Angelo's in Philly. What you want to get is: the cheesesteak, with the long hot whiz, and extra cheese, with onions. Most cheesesteak places you want to get cooper sharp, which is sharper like a farmer’s cheese but American so it melts easy, but at Angelo's, which is my favorite cheesesteak, you get long hot whiz. It’s tied with this place Max's, but Max's is more about the experience and the [Angelo’s] cheesesteak is better.

Watch Frank Hurricane’s Mystical and Musical Journey from My Home on PBS.

Catch Frank Hurricane on tour—he’s got a long list of upcoming shows.

Good Reads

Glossy, Gunky, and Ready in Minutes: AI Meal Recipes are Overrunning the Internet, Ali Domrongchai for Defector

Three Potpies That Go Beyond Chicken, Nikita Richardson for The New York Times, “Where To Eat: New York City”

“It has taught me about my own taste, expanding what I am drawn to and encouraging me to delve deeper into my favorite movements, periods, and artists. It has taught me to worry less about seeking out the "best" version of something and instead focus on the beauty of whatever is right in front of me.”

The Wonder of the Regional Art Museum, Megan Greenwell for Defector