#53: A Conversation with Julie Rae Powers

Queer Appalachian photographer Julie Rae Powers discusses their new book DEEP RUTS.

This newsletter is the last of the year before an exciting revamp. Weekday Warriors will be back in your inbox in 2025 with a return to its original form that started it all: an original recipe and some music for the time it takes to make it, as well as a few new perks. It will include a hotline for cooking questions, a dip into a vast archive of vintage, family, and community recipes, and a brief conversation with someone who inspires me creatively (like this one). It’s an honor to round out the year by sharing this conversation with Julie Rae, and I’m so excited to share more with you all where this—and more—came from.

In January of this past year, I had the good fortune of speaking with photographer Julie Rae Powers over Zoom. Born in Williamson, West Virginia—though claiming both Virginias as home—they currently live in Columbus, Ohio with their partner. We talked about their new book, DEEP RUTS, a compilation of portrait and landscape photography contending with standard notions of Appalachian identity (published by Platanus Editions in April 2024).

DEEP RUTS is a triple entendre alluding to the deep-running roots of religion, deer in rut, and mind-ruts that govern our thinking and carve out our daily lives. It’s also a really beautiful picture of a shifting Appalachian landscape, both culturally and physically.

Earlier this fall, Hurricane Helene tore through Western North Carolina, Northeast Tennessee, and Southwest Virginia, displacing and uprooting people and communities in ways unimaginable for flooding in these parts of the mountains til now. Since then, I’ve reflected a great deal on our conversation and something Julie Rae called “saturation” of certain norms that hold us down or hold us back—but also the subtle, tactful subversions of them in Appalachian culture that lends courage and imagination to break free of systemic ruts there and everywhere.

Powers’ work has since been featured in Oxford American (“An Archive Of One’s Own”) and in an exhibition “Scatter These Hills With Beauty: Queer Appalachian Art” at ROY G BIV gallery, curated by Marcus Morris. I’m very happy to finally share the interview now. It has been edited and condensed for clarity.

CJ: Tell me about your photography life and when it began for you.

JRP: I took all the art classes I could in school. I really loved it, but I was really bad at it. I was trying so hard to be good at drawing [and] painting, but I wasn't really making a lot of progress. My high school art teacher was like, Dang kid, you really are trying, you're just not getting anywhere. It was disheartening to hear this type of truth. I'm still not sure it was the most appropriate truth, but I was like, Okay, well, that's sad.

Around that time, my friend Mallory had an interest in photography and a natural knack for it. We’d go on these little adventures, and a few days later get the prints back or she would put them on MySpace. I remember being like, Well—this is fun, I have to do this. So I grabbed my dad's Kodak point-and-shoot and started taking pictures. I practiced for a while and picked 5 or 10 to take to art class one day—I think this must have been a year or so after this conversation [with my art teacher]. I handed them to her. She flipped through them—raising her brow—but then she looks at me smiling. She was like, Oh, you found it. And I was like, Boom.

CJ: How did that feel when she said that?

JRP: It was really affirming. She was originally from New Jersey, living in the South and raising her kids in the South, and I was a soft little squishy Southern kiddo—very sensitive. Her disappointing me like that really sucked, but getting her approval after that felt very good as a teenager. I also respected her in this way, that sternness, structure, honesty. I grew up with an aunt who was very much like that, a school teacher as well. She's in her 70s and still substitute teaching. So I think I was responding to [the sternness of] my teacher in a similar way as my aunt.

CJ: How did you choose images to print to show her? How do you choose them today, like selecting the ones that go into DEEP RUTS, for instance?

JRP: When I was picking out the ones to show [my teacher] I wanted range, but I also want to show her some stuff that might be similar to the type of thing she painted. And also the ones that I just gravitated to, like the saturation of a bicycle seat or something.

For DEEP RUTS, it’s much more complicated. It's my own personal narrative of over 10 years with thousands of photographs. It was this big ambiguous sphere: How are you supposed to put such a dynamic human experience into a book of photographs? I struggled with that forever.

The choosing is hard, because it's 13 years of photographs at this point. Thousands of photographs. There's been probably 10 different iterations of this project. Eventually I had to create and implement a structure for myself. I think a lot of the things we're interested in we actually start writing about or photographing or interacting with a lot sooner than it becomes obvious to us. Religion is a huge part of that journey. A lot of that [interlude] comes from shame and growing up in a very religious, conservative setting.

So I decided to break it up into stages, chapters, or portfolios that are biblical references: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

JRP: The Father is literally my father, a [section that] is about fatherhood, masculinity, guns, hunting, landscape: this grotesque violence that it takes to hunt and provide for your family, but also respectability. There's rules and values that they operate by, an industry. That's the first portfolio, and it's all in black and white. I use that as an illustration of more traditional ideas that are not working for me. Not necessarily passing a judgment, but [depicting] a highly saturated world that I was put into. It’s one of the longer chapters.

JRP: The [second chapter] is the son, which is me. It’s a play on gender and queerness, on Jesus. That whole portfolio is 10 years of self portraits that I've done of myself. They're not chronological, but you see me age as a person.

JRP: The Holy Ghost is the third [portfolio] where I think about landscape as this beautiful thing that is appreciated and revered and loved. Mother Nature is the divine feminine, but also motherhood, my mother, domesticity... It’s in full color and a more vibrant, saturated portfolio. You see how the book starts off in total black and white, and then ends up in these vibrant colors, which for me is a timeline of my experience. I come out, and it's really difficult, contending with some of those traditional [black-and-white] values. Over the years, there's development of the self, but also of relationships with my parents. It depicts different iterations of ourselves, growth, and a betterment of life. So that's how I chose the photos.

CJ: Wow. Well, I love that. I’m curious about “the Father” section, and your choice to start with black-and-white photography. I love this idea of color increasing or expanding as the narrative moves into the Son and the Holy Ghost. Do you set out to photograph either in black and white or color? Do you decide that later or do you do that while you're out in the field?

JRP: Sometimes turning a photo black and white is just an aesthetic choice. It might look better—or you can see my photographic mistakes more in the color. Sometimes it's just prettier. When I'm shooting digitally and only digitally, I shoot in color and then I will choose black and white [later]. Sometimes a photo will be a color photo for five years and I'm like, Nope, let's try it like this.

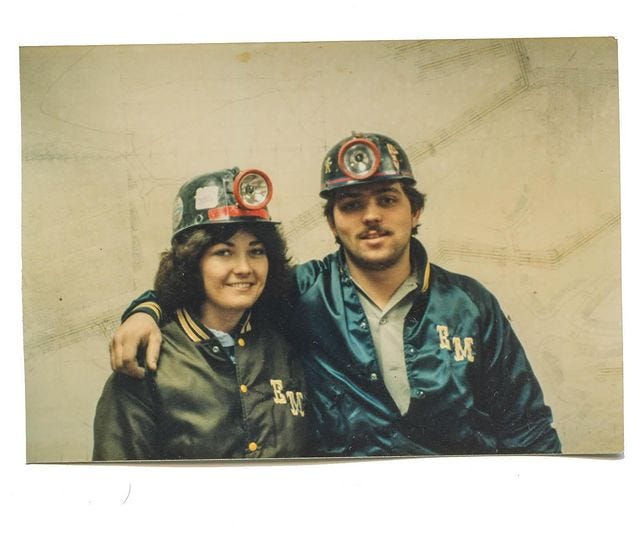

CJ: I love the idea of the physicality of the archive being more accessible than the digital—that there’s still use to this concept in 2024. There's something that you shared on Instagram, a photo of your parents in mining helmets, where you said that you don’t think that DEEP RUTS would have been possible without this photo being a gift from the family archive.

JRP: There's always those pivotal moments—and I've got a handful of those—where I can really point to the development of this project. This is definitely one of them. I remember the first time I saw it, it almost felt mystical or mythical. I was so struck by the image, but I didn't really have the language for it or know why. I looked at it and I sat with it. Then I really just put it away. Over time, I would go back through this [physical] archive. It really was just two or three cardboard boxes of loose images over the years. I would return to these boxes, whether I looked through [them] once a week or twice a year or whatever.

JRP: I think developing a relationship with that photograph [of parents in mining helmets] is really what allowed me to start peeling back some layers and realizing how layered my experience has been as a personal narrative—me as a person who had this experience between 2013 and now—but also contextualizing our experience as a family with me in it. For example, it's interesting to zoom all the way out and look at the historical timeline: I was born in 1989 in one of the poorest states in one of the poorest counties to homemakers and coal miners. That really tells us a lot about what was going on at the time. I literally was born in a hospital on a hill that overlooks a train yard full of coal cars. I was born into this saturation.

JRP: [This photo of my parents] helped me contextualize my experience historically. We were white people in the 90s in West Virginia. That's a totally different experience than the Black experience at the time, right? Really considering all the circumstances: economic, historical, political—all these things. Then I realized that the photograph [was] literally made before I was born—like, right before I was born. To me, this photograph is part of my origin story. Not only am I a photographer, but I'm also interfacing with the photographs of my own family archive. I've made my own personal family archive from my perspective. I think having that photograph was just key to these realizations about my experience in the work.

CJ: You mentioned ‘saturation’ several times, both to talk about the color but also composition and theme—that's probably not the right way of putting it in technical terms—but, what does saturation mean to you?

JRP: I think when I'm talking about saturation of culture, objects, or iconography, it’s the physical presence of coal being everywhere that informs the experience—and also informs the politics that come. When I say saturation, it's this idea that [coal] is everywhere and that it can become this overshadowing thing that feels like there’s not room for other aspects of life.

Masculinity was [also] everywhere around me as a child. I was a very genderqueer kid from the jump. Part of that was economic. I was wearing like hand-me-downs from my boy cousins, but I also think there was just this natural embodiment of this thing [masculinity] around me.

JRP: These gender categories are such a farce, right? Even the more “feminine” people in my life were very masculine or not participating in femininity in a mainstream media cultural ideal. My mom was like, Makeup's stupid. She sold Mary Kay for a while, but she was like, I'm a woman, whether I wear makeup or not. I'm wearing Carhartt. I'm doing my thing. The saturation of [strict] gender categories is interesting.

“When I'm talking about saturation of culture, objects, or iconography, it’s the physical presence of coal being everywhere that informs the experience—and also informs the politics that come.”

I’d think, Well, of course I grew up to be a butch or genderqueer person. But then: Wow, I have been punished for it in my adulthood—where it was allowable or fluid or maybe only slightly contended with in childhood. I think I use the term saturation as [meaning] overwhelming or constantly present. Unavoidably present.

CJ: It's subversive, your mom's comment, or even that framework. That gender norms exist somewhere, but they don't need to exist here right now.

JRP: I think of saturation towards the end of the book [differently], being that my life is now saturated with things I didn't think I could have. There's a celebration in that. I love to be saturated with those good things or the things that align with me—but it felt like [the past] had to remain separate, like masculinity and Appalachian culture and my dad versus my queerness and bright, beautiful things and reverence for the natural world, right? But they actually do and can coexist. That doesn't mean that there's not conflict—there's certainly conflict—but it's just nice that I've been able to create my own conclusions about life, instead of all the things we're told. That's what the book is about.

CJ: Tell me about the title DEEP RUTS.

JRP: DEEP RUTS is a multi-entendre of sorts. Inside the book there’s a lot of deer iconography. This is imagery I saw all the time as a kid: in hunting or home interiors catalogs, the types of art we would buy to decorate the house, a buck [designed] blanket … So one [definition applies to] deers in rut, its seasonality and the masculinity.

There's land ruts. I think about how coal mining makes a rut into the mountain, or down into the earth, or how deer tracks make ruts in the woods. Paths and ruts from cows walking, or from four wheelers—or whatever.

But [there’s] also deep ruts as in getting stuck in our ways and our ideologies, accepting the stories that we tell about each other, that we tell about ourselves, that the media says about us. I think about the deep ruts of religion, how it can create a stubbornness that keeps connection and understanding from happening. I'm not particularly a religious person, but I have my own ideas about coexisting as a queer person with religious people. Once we start thinking something is true, it carves into our brain, and it's really hard to get off of that path and carve a new way of thinking. So when I think about those things I was like: This is the title. Boom. All the things. All the ruts.

“It felt like [the past] had to remain separate: Masculinity and Appalachian culture and my dad versus my queerness and bright, beautiful things and reverence for the natural world, right? But they actually do and can coexist. That doesn't mean that there's not conflict—there's certainly conflict—but it's just nice that I've been able to create my own conclusions about life, instead of all the things we're told.”

CJ: That's amazing. I like the idea of ruts as stubbornness too. I hadn't thought about it like that.

JRP: Whenever someone's like, Oh, well, how's your life going? It's like, Just stuck in a rut, dude. I'm stuck. I can't move forward, I'm not moving forward. I'm stagnant. There was a period where my relationship with this place [Appalachia], my parents, and my culture, was stuck in a rut. There was this tension and contention and avoidance and despair and grief. And it was really arresting for a long time.

CJ: Writer Kelsey Sucena writes a fiction piece at the end, which is a cool switch-up. I'm curious about other Appalachian artists or people who aren't photographers who inspire you in a similar ways, in thinking about the futurity and possibility, this Holy Ghost world that you've created in context.

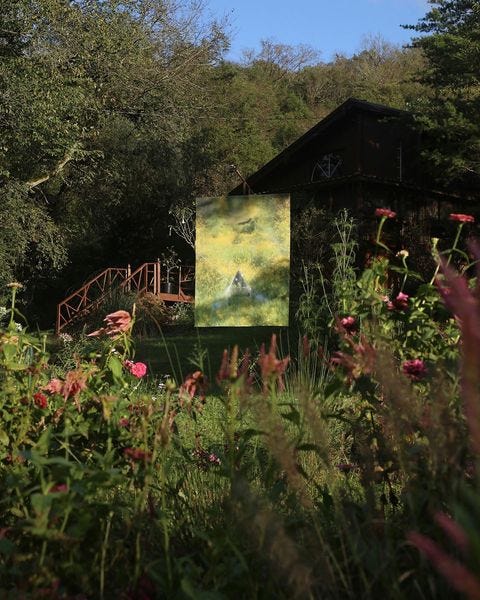

JRP: Yeah, a direct inspiration of some of the beauty and saturation towards the end of Deep Ruts would be a photographic artist named Benjy Russell. He's Indigenous Choctaw and lives in this beautiful cabin in the woods in Tennessee. He lost his partner some years ago at a young age. He's made this art installation at his home at the cabin [where he] and his friends have picked flowers that come back every year. They mixed the flower seeds with his partner's ashes and created this garden. Upon the first bloom, Benjy—and he has a written piece about this and does photographic installations, which I'm getting to—but upon the first bloom, he goes and spends time talking to the garden, to [his late partner] Sterling, and really thinking about grief and death and processing that as a queer person.

CJ: Very moved by that.

JRP: It's so moving. It’s so moving. And the photographs of the bed, the flower bed, are gorgeous.

All over his property, there are lots of flower beds, and he will print amazing, vibrant, reflective, fun images with neon or glass and mount them in his garden. It's a whole photographic experience. He invites folks from his community, either the local community or his wider art community to come experience the garden when it's in bloom. That was so moving for me, thinking about how beautiful this space is, but also how loaded it is with grief for him. It’s not a one-to-one, but I relate to that. That has definitely been an inspiration to me in a direct way.

JRP: There are lots of other Appalachian painters and photographers [ who inspire me] from a way-they-live-life approach. Someone who really inspires me is the photographer Shauna Caldwell. She’s an arts educator at the Turchin Center at Appalachian State, and she was born and raised just outside of Boone. Growing up, she was sent the same messaging: If you want to do anything with your life, you’ve got to move out of here. You’ve got to go to the big city, in particular, if you want to be an artist or you want to be queer. And she just straight up said, Nope, I want to be home, I want to change things in my community, I don't want to leave. She really has built her own life there as a queer person living on the family land that she grew up on.

And she's thriving, is the thing. We're told we cannot thrive, and I really admire that conviction of doing it her own way. She makes a lot of art about her relationship with the land and with the herbs and the flowers and the meanings that they make in her life and her peers’ lives.

CJ: If you were to host people for dinner, a dinner party, or even just have people over to eat within the theme of this book, what would you serve?

JRP: It would be breakfast for dinner. A little cubed venison in the iron skillet with fried potatoes, and eggs. It would be breakfast for dinner, because my family has made this for me, and my dad makes it for me [still] sometimes. When we would be at the hunting cabin as kids or even as adults, there was venison around, and that would be dinner for everybody. And that really encompasses the experience of this book.

CJ: That's great. That's awesome. I like the cast iron skillet detail.

JRP: Yeah, it's part of it. You can't just fry up venison in a regular pan. It's not gonna taste the same.

CJ: No, it's not the same.

JRP: There's literal—you know this, you're a food person—there's science that proves it.

CJ: Science, yeah!

JRP: People who don't like venison, they’re not cooking it right. They're cooking it on a nonstick skillet. It ain't right

Get DEEP RUTS for yourself or a loved one—makes a great gift for the holidays, no?