#50: Canned goods, country roads, and poetry of witness

"These are the roads to take when you think of your country"

I recently put on my big boy britches and watched HBO’s Last of Us alone at night time (please clap). In episode 4, heroes Ellie and Joel share a twenty year old can of Chef Boyardee in the tenuous wilderness. “What is this?” Ellie asks, because she was born into a world where Chef Boyardee doesn’t exist. Joel, who has known life before the apocalyptic episode that hurled them into a world of eating old, mysterious canned food, tells her that it is called Chef Boyardee. “That guy was good,” Ellie says, and Joel agrees.

This particular episode came at a time that I was listening to a lot of the song Canned Goods by Greg Brown, which is about the delights of tasting foods of the summertime in the wintertime—of the past in the future—and his grandmother who deftly cans green beans, peaches, pickles, tomatoes, blackberry jam, and all the other things that come with it. “She’s got magic in her, you know what I mean/ she puts the sun and the rain in with her green beans.” In the case of The Last of Us, the can was no doubt manufactured in a sterile environment and pumped with various stabilizers, etc. But it came in handy for survival, for humor, and, for Ellie and Joel, a faint glimmer of spaghetti and red sauce. For you and for anyone, I wish a little taste of the sun and the rain this week, even if it’s from a jar of Bonne Maman or a can of spaghetti-O’s.

Piece of Power

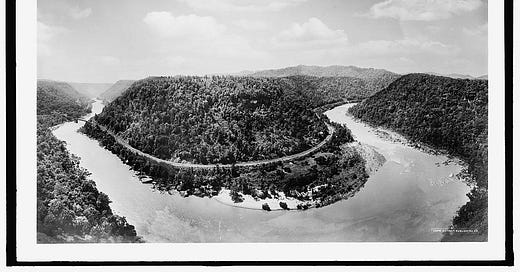

Consumed by the news, so much of it traumatic, I find myself returning to The Book of the Dead by Muriel Rukeyser, a narrative collection of poetry that documents the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel Disaster, a case of large-scale, imminently fatal lung disease of workers who built the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel in Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, in 1927. To generate power for the chemical company Union Carbide (does this sound familiar?), New River Power Company signed off on a plan, contracted by construction company Rinehart and Dennis to divert the New River and build a tunnel to reroute it under Gauley Mountain. About 3,000 men, looking for work, moved to West Virginia where they mined the sandstone. They weren’t given any protective gear, were treated horrifically and payed dismally. Black workers, making up about 3/4 of the employ, received worse treatment, later testifying that they were denied breaks and forced to work at gunpoint. Sandstone is made up of cemented quartz, or silica. With prolonged and direct exposure to the silica dust, workers (none of whom had masks or any protection) suffered from silicosis, and a number of them died within a year.

Despite being one of the biggest industrial disasters of the 20th century, despite the scale of the tragedy and all of its gross injustices, the event is not widely or popularly known. Much of what we do know about it, though, we glean in detail from one single book of poetry. Muriel Rukeyser’s social justice writing and reporting was remarkable and vast, including the Scottsboro case in Alabama where she was arrested in the process (the poem “The Trial” was published 1933) and via Barcelona during the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. Her archive is full and rich, and The Book of the Dead remains one of her most famous and widely published texts; it is considered a prime example of “poetry of witness” a term coined by Carolyn Forché to mark the social space that arises between the personal and political, people and events. It is, at its core, the acknowledgment of a traumatic event, or the trace of it.

I bring up the Book of the Dead because the site of its tragedy is also the site of a new one almost 100 years later: the New River is part of the Ohio River basin that will bear the brunt of the Norfolk Southern train derailment and subsequent burning of toxic chemicals like vinyl chloride in East Palestine, Ohio. I bring it up because in it, interrogations and court proceedings are meticulously recorded, map-like. It’s also a text that invites action through redirecting attention: walk this new way, look around here, and see. “These are the roads to take when you think of your country,” Rukeyser writes. “and interested, bring down the maps again/Past your tall city’s influence, outside its body: traffic, penumbral crowds, are centers moved and strong, fighting for good reason.”

In 2016, Catherine Venable Moore traveled to her hometown of nearby Fayette, West Virginia to follow and effectively retrace Rukeyser’s steps (Moore’s longform essay about this for the Oxford American is also the introduction to the recent reissue of Book of the Dead.). In it, she uses past poetry of witness to navigate her personal past and the present world in a new way.

Various timelines churn out one or both of two urgent messages, my own voice so often part of the same widening echochamber: 1. something bad happened that’s even worse and more incontrovertible than you could have ever imagined and 2. here’s what you can do to help. When I’m overwhelmed, I consider a line from the title poem of Book of the Dead that provides alternate instruction: maybe what not to do is actually a better place to start. It hangs in my head softly:

What three things can never be done?

Forget. Keep silent. Stand alone.

Other great things I’ve read since last time:

Jaya Saxena writes about culinary gatekeeping, Twitter jokes, and loving something (food) so much you don’t want others to have it. This is a a complicated “toxic love” they suggest, where racism and capitalism fuel the idea that recipes can be definitively owned or claimed, noticeably when Black and diaspora dishes gain mainstream attention.

Helena Fitzgerald on bad coffee, which is also my favorite type of coffee after good coffee. In the classification, there’s Road Coffee, Gas Station Coffee, Church Coffee, The After Dinner Coffee at Someone Else’s Parent’s House, and Night Coffee: “Coffee after 8pm technically counts as drugs.”

Marian Bull on the delights of the over-easy egg. The key is a cast iron skillet and losing the fish spatula for a silicone one, a “flip and dumper.” The original AI chatbot (the eldritch astrological app Costar) advised me recently that “you don’t have to know everything about someone to love them.” You also don’t have to know everything about the egg or all at once; the yolk, a lot like something to behold over time, is just as well concealed and better to reveal itself slowly.

Vinson Cunningham, Naomi Fry, and Alexandra Schwartz in conversation on the state of the Rom-Com. If the subject of the Rom-Com is something that you, like me, think about regularly, you’ll devour it. A highlight:

AS: I feel like I’m officiating a weird wedding in making these comments. I’m, like, “Love is epistemological.” [Laughs.] But it’s true! It’s about knowledge of the self and the other. It’s about building up the ideal, only to find that the ideal can’t be sustained and preferring what comes after the ideal is washed away. That is what love at its best is, and that’s what rom-coms can give us.”

NF: Which is why not taking off the mask but putting on another mask—the Twitter-esque “I see you, I hear you”—is not working. People aren’t revealed to each other in their frailty and their desperation and desire. It’s complete falsity.

…

VC: There’s a big difference between reflecting social change and trying to, like, discourse about it. In some ways, the rom-com is a consequence of a new social possibility; it doesn’t need to comment on it.